When the New York City Coalition Against Hunger announced in late January that they were rebranding as Hunger Free America , the Hagstrom Report—a federal agricultural policy newsletter—reported that the move was “financed largely with a grant from the Walmart Foundation .”

Some advocates immediately started trading gossip. After all, doesn’t Walmart create the kinds of problems that anti-hunger groups try to solve? Or is there a role for big business in the fight against hunger?

Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America and the author of All You Can Eat: How Hungry is America? , says he only accepts funds from corporate donors that “[don’t] come with strings attached,” meaning that funders don’t determine the projects or opportunities that the organization pursues.

“I’m neither defending or critiquing Walmart,” Berg says. “Their policies are pretty standard for retail.” No one bats an eye at other big-box stores like Target that have similar philanthropic and employee policies, he adds.

So why all the fuss about Walmart? Sure, their philanthropic giving is a strategic business tool, funneling increased funding to communities where they wish to enter the market. Walmart donated an impressive 630 million pounds of food in 2015. In 2014, Walmart and its foundation gave $1.4 billion in cash and in-kind donations globally, including grants to “provide training, education, and career pathways for U.S. retail workers.” They’re hardly the only ones to do so, however: Bank of America, National Restaurant Association, Arby’s, and Kraft Foods are all big supporters of anti-hunger groups.

The catch is that as one of the world’s largest retailers, Walmart controls nearly a quarter of all grocery sales in America; their Goliath market share allows them to set standards in the retail industry. They have “pioneered” strategic practices like part-time arrangements, temporary workers, and unpredictable schedules that are often at the root of poverty and hunger.

“[Walmart] is creating poverty by eliminating jobs in communities through off-shoring manufacturing, closing small businesses, and driving down standards in the supply chain ,” says Eddie Iny, Program Director at Organization United for Respect at Walmart , a group of Walmart workers who are pushing back and organizing themselves—even if they receive reprisals such as write-ups or reduced hours for speaking out. “They pay workers poverty wages, which is generating poverty in America. Their poverty footprint is tremendous.”

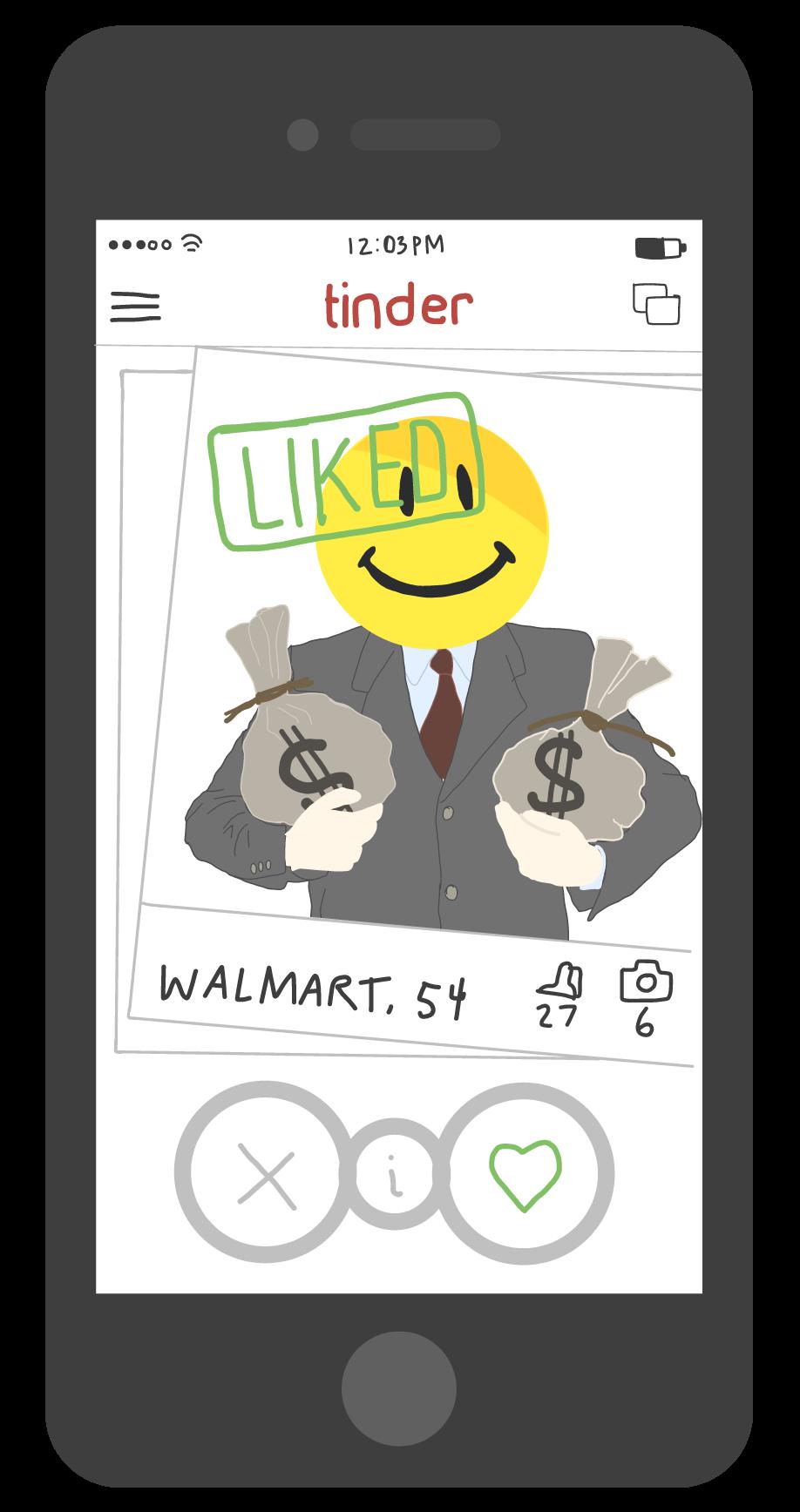

Walmart may not be the best match to fund anti-hunger organizations, but many are still swiping right. Illustration by Kyle Sheehan

Walmart may not be the best match to fund anti-hunger organizations, but many are still swiping right. Illustration by Kyle Sheehan

Seems a bit counterproductive, doesn’t it? Anti-poverty activists generally advocate for living wage jobs, affordable childcare and housing, and the strengthening the government safety net. Walmart, meanwhile, employs a cadre of lobbyists to keep their employment practices in place. They spent $12.5 million in 2014 alone to influence issues like the minimum wage, social security, taxation, and economic regulation. They also contributed $9.5 million to presidential and Congressional candidates on both sides of the aisle between 2000 and 2012.

Joann Lo, co-Director of the Food Chain Workers Alliance —a coalition organizing to improve wages and working conditions for members who farm, process, and prepare food—expressed concerns shared by some of her colleagues in the labor movement that groups may be legitimizing or allowing Walmart to greenwash or “fairwash” their image by accepting their donations.

“Is it a tactic by Walmart to divide an already not super cohesive movement ? There are varying levels of commitment to broader social justice goals among anti-hunger groups . If one recognizes why there’s a need for the services of anti-hunger groups—why there is hunger—it’s poverty,” says Lo. “How are you going to address poverty? The concern is that corporate donations make groups hesitate to take action to address poverty directly.”

Andy Fisher, a long-time food activist and author of the forthcoming Hunger, Inc. , sees it another way. He argues through his examination of funding in the anti-hunger sector that funding relationships could potentially give nonprofits a platform to shape business policies. He cites shifts in funding policies over the years from food acquisition towards more nutrition and policy work, such as sourcing healthier food, nutrition education, and connecting people to government nutrition benefits and tax credits.

With mascots this cute (and profits this large), how could non-profits say no? Illustration by Kyle Sheehan

With mascots this cute (and profits this large), how could non-profits say no? Illustration by Kyle Sheehan

There have been some encouraging signs that the influence goes both ways; most recently, Walmart raised wages in response to mounting pressure from organizers and the public, but they did not respond to requests for comment. For many of their employees, like Dave Alvarez, it’s too little too late. Alvarez, a Walmart associate in the produce department at the store in Lutz, Florida, describes packing up boxes of donated produce on the job for the local Feeding America food bank.

“The pay is so low, I turn around and go collect what I packed,” he says, adding that he and his peers often subsidize their hourly wages with food stamps. When the pay raise went into effect, part-time hours were cut. “That’s all they hire people for,” he says. Trying to support himself and his pit bull mix puppy with gas and other expenses, Alvarez is grateful for food providers, and places the blame on Walmart.

“There’s no excuse for this,” he says. “This is the wealthiest corporation on the face of this planet. They can pay a living wage.”

To him and other associates who are members of OUR Walmart, the fight is about dignity and respect. Many say that the time has come for some deep soul searching in America.

“We have forgotten how to bring people to the table and have relationship building conversations,” says Matthew Habash, a former member of Columbus City Council and CEO of the Mid-Ohio Foodbank . “The debate about the wage scale in this country is bigger than any one company. The scale at the bottom needs to come up. We need to value service jobs as much as management. If service workers didn’t work for a day, what would happen? And I think if those making over $100,000 didn’t, we wouldn’t notice.”

Ultimately, it seems that organizations align funding with their vision for social change: groups that support incremental change and public/private partnerships see corporate donors as important partners that allow them to do their work. Groups that support social movements and economic justice as the key drivers of change are more likely to decline relationships with corporations.

To put the largesse of corporate donors in perspective, it’s useful to note that 5% of charitable giving comes from corporations, 15% from foundations, and 72% from individuals, according to Giving USA’s annual report on philanthropy. Anti-hunger groups could demand more from corporate donors in exchange for their provision of community goodwill and tax deductions. They could insist on transparency about lobbying efforts, facilitate conversations with organizers, or help create standards for social responsibility like the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ Fair Food Campaign or Restaurant Opportunities Centers United’s High Road to Profitability. Perhaps because of increased pressure to grow , few are willing to do so.

After all, like any relationship, it’s complicated.