Real Talk is our weekly series about the peaks, pitfalls, and perils of the food world. Every week, we’re taking you to the heart of food’s most glamorous (and difficult) projects with the help of our content partner MOO , whose products are all about making dream hustles into beautiful realities ( click here for 20% off your next order!)

From pop-up dinners to pop-tart marketing, hyper-local restaurants to global food empires, this is your peek behind the curtains of food & drink’s dreamiest initiatives and get—you guessed it—the real talk. This week, writer Cat Lamb lets us in on her crazy ride from home cook to pop-up dinner expert. A lack of wine glasses and experience didn’t stop her and her partner from creating one-of-a-kind dining experiences in the South.

_____________________

Saying that I got into the pop-up game on a whim isn’t quite accurate, but it isn’t that far from the truth, either.

I have worked in food for roughly six years, doing everything from baking wedding cakes to making cheese to writing about what we eat. In fact, I first started attending pop-ups in my hometown of Charleston, South Carolina because I was reporting a story. I continued to volunteer at dinner series because I couldn’t afford to attend most of them otherwise, and they made some damn good food. The people who put them on were so consistently passionate and inspiring, and seemed to have such a good time during the event, that a very dangerous idea started to form in my head. Maybe I could do this sort of thing, too…

Of course, I needed a partner. So I texted D.J., one of my best friends and a true go-getter, which led to several phone calls, meetings over beer, countless lists in tiny notebooks, and a plethora of emails. In the end, we decided: “Why not?”

We knew that we wanted our pop-up series to be very inclusive, price-wise and otherwise. But we also wanted to make it more valuable, more important. We wanted them to have some bigger significance or goal — and I had an idea about what sort of direction we should take.

I had first heard about Dan Barber’s WastED pop-up restaurant when it was covered by my former colleagues at Food52. It was such a simple, genius concept. Barber was taking food that would normally be thrown away and making it into something that was not only edible, but delicious — and starting a dialogue about a huge issue in our food system to boot.

Pogoing off of this theme, D.J. and I decided that each of our dinners would teach our eaters about a different aspect of the food system. All that was left was to choose a name. D.J. pitched “Amateur Hour,” which was the perfect moniker for a duo delving headfirst into the world of pop-ups with veeery little experience.

D.J. and I figured things out (sort of).

D.J. and I figured things out (sort of).

With our “brand” set up, we started to organize our first dinner, which was going to focus on food waste. We needed the practical stuff: plates, wine glasses, cutlery, etc. All previous pop-ups I had worked had simply rented out table settings, but we were in no financial position to do that. So we spent a few hours picking through the nearest couple of Goodwills, and left with a charmingly mismatched set of about twenty plates, bowls, wine glasses, and silverware, which we then washed (through several cycles) in D.J.’s dishwasher.

We then started making some house calls to source our ingredients. I somehow finagled a call with Irene Hamburger at Blue Hill to get some advice on the pop-up, and she was very helpful, though she seemed skeptical that we were going to pull the whole thing off in a month. We visited farmers markets, grocery stores, bakeries, and cheese shops to source our ingredients—many of whom turned us away. In the end, we accrued enough ingredients so that 75% of the food we used in our dinner would have otherwise been thrown in a landfill.

D.J. locked down a coffee training center as our venue. We made an Eventbrite page , set up an email account, and started promoting ticket sales via social media. We even got a few local sites to give our event a shout-out. Finally, all that was left was the actual cooking. The coffee training center had a pretty minuscule kitchen, so we decided to do prepare everything beforehand and simply warm our dishes up there. We spent two intense days cooking, turning D.J.’s kitchen into a war zone of cutting boards, knives, and herbs EVERYWHERE.

Finally, the day of the pop-up arrived. We had sold out of tickets (despite my nail-biting that we wouldn’t). We loaded up the car, drove to the training center, and started setting up—and then time went into hyperspeed. Suddenly it was thirty minutes before go time, and we hadn’t yet covered the tables in butcher paper, much less set the tables. D.J. was still working on writing the menu.

Somehow everything came together before the first guest arrived. With the magic of BYO beer and wine, everyone started chatting over our sautéed mushroom bruschetta. D.J. and I began warming things in the kitchen, which was open and faced our guests’ tables. Finally, our guests sat down and we served the soup. Then came our first mistake: We had decided to show a seven-minute clip of John Oliver speaking about food waste. No one ate their soup. The sound wasn’t great. The conversation came to a halt. Afterwards, it started back up, but we learned not to interrupt the flow.

Our guests enjoying the fruits of our Amateur labors.

Our guests enjoying the fruits of our Amateur labors.

The main course, a frittata of salvaged squash made with undersized eggs, cabbage salad, and an array of roasted vegetables leftover from the farmers market, went over well. Then it was time to serve dessert, a trifle made of layers of leftover cake from a local bakery, custard, and candied lemon rinds sourced from a lemonade stand. Finally, we started cleaning up—and what an epic cleanup it was. We washed everything in the small sink of the training center, stacking whatever dirty dishes we couldn’t get to back into bags to take home and wash. People hung around, asking if we needed help, which we did but couldn’t ask of our guests. From then on, we kept the cleaning very separate from the party.

After we finished loading the dishes into the car, we went to our neighborhood bar for a drink. By the second cocktail, we were already discussing our next dinner. We settled on a “utensils” theme: focusing not on what we eat, but how we eat it. Each course would require a separate utensil (bread for our homemade pita with burnt eggplant dip, chopsticks for our vegetable dumplings, fork/knife/spoon for cauliflower steaks on cauliflower purée, and hands for our gingersnap ice cream sandwiches with homemade coffee ice cream). This dinner was our most ambitious, menu-wise—but also the easiest to pull off, since we held it at the coffee shop where D.J. and I both work, so we knew the owners and kitchen well.

Our coffee shop showed Amateur Hour some serious love for our second event.

Our coffee shop showed Amateur Hour some serious love for our second event.

For our third dinner, we made a meal based off of what the Pilgrims and Native Americans actually ate on the meal that became known as the First Thanksgiving. We only used ingredients that would have been accessible at the time, so no potatoes, sweet potatoes, butter, sugar, flour, etc. The outdoor venue made this event especially complicated since we could only heat our food on one grill. Also, since we were acting as a pseudo food truck for the evening, anyone could come and buy a meal from us, so we weren’t sure how much Wampanoag stew (made with sunchokes, greens, and polenta and thickened with chestnuts) to make. In the end, everything went swimmingly — except for a minor fiasco in which our popcorn wouldn’t pop over the meager heat of the grill, leading us to cross the hotly anticipated “Pilgrim Popcorn” off the menu.

Sorry folks, no Pilgrim Popcorn tonight!

Sorry folks, no Pilgrim Popcorn tonight!

Our most recent dinner, which took place at the end of February, focused on the issue of food deserts and what we as eaters can help do to eradicate them. The precise definition of a food desert is difficult to pin down, but generally they are areas without access to fresh, healthy, affordable food. Charleston and surrounding areas have their fair share of food deserts, and most are closer to wealthier neighborhoods than their residents know. For this event, we teamed up with the Lowcountry Food Bank to serve a four-course dinner cooked solely with ingredients sourced from local food deserts. A portion of each ticket sale went towards advocacy projects for nutrition.

We decided it was important to host this dinner in an area near a food desert, so we partnered up with the lovely, hirsute folks at Frothy Beard Brewery. Not only were they incredibly helpful, but their beer is great and took care of the BYOB issue. We spent a lot of time sourcing ingredients at nearby dollar stores and convenience marts, and spent even more time brainstorming a way to use said ingredients in a creative, semi-healthful way. We settled on a menu of chili-roasted chickpeas, Caesar-style deviled eggs, sweet and salty gnocchi with peas, and PB&J pie with homemade Cracker Jacks. The food deserts event seemed to go the most smoothly of our dinners, perhaps because we had more experience from which to draw.

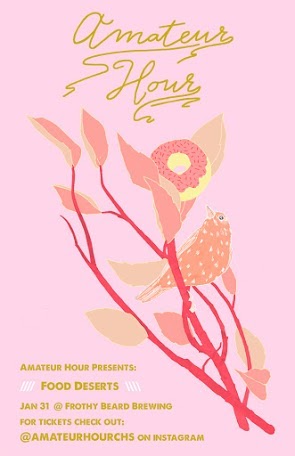

The poster from the most recent (and slightly postponed) Amateur Hour.

The poster from the most recent (and slightly postponed) Amateur Hour.

I don’t think we could have pulled Amateur Hour in such a limited time, and with such limited experience, in a town other than Charleston. We have such a tight-knit food scene that people really wanted to help us out—and, since D.J. and I both worked in the food and beverage industry, we had plenty of connections and favors we could call in. Our friends also came through big-time to support us.

What does the future of Amateur Hour hold? Hopefully more dinners about what we eat and how we eat it. The fact that there are only two of us organizing the event, cooking, and serving the food, which limits the size and frequently of our dinners, but we don’t do everything by ourselves. We draw on our friends, our community, and late-night Oreo eating to get us through.